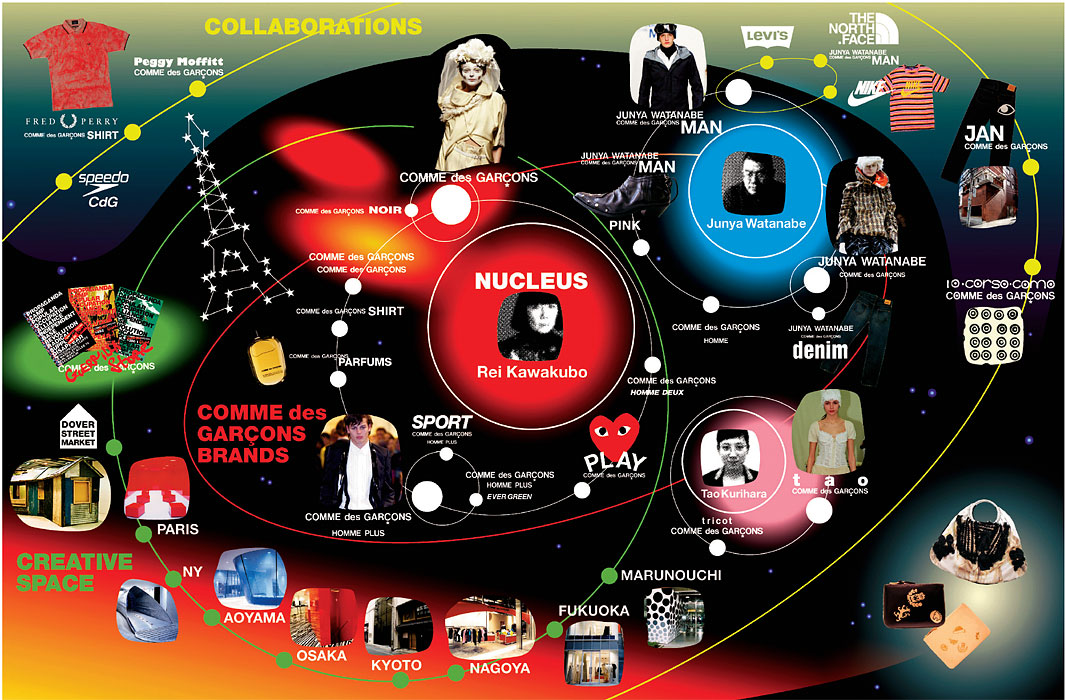

The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

Page 1 of 1

The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

Let's explore and discover the deep Universe of Comme des Garcons and Rei Kawakubo.

one of my favorite little descriptions is this one:

it is a bit outdated since they already operate 3 Dover Street Markets - London, Tokyo, NYC.

one of my favorite little descriptions is this one:

it is a bit outdated since they already operate 3 Dover Street Markets - London, Tokyo, NYC.

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

The Challenge of Rei Kawakubo old japanese documentary on the house of Comme des Garcons

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

A downloadable pdf booklet with great description of Comme des Garcons concept

DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET HERE

DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET HERE

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

Re: The Comme des Garçons "Universe"

An interview with Rei Kawakubo at STYLE.COM:

http://www.style.com/trendsshopping/stylenotes/040113_Style_Print_Rei_Kawakubo_Comme_Des_Garcons/

Chaos Theory

Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons says she isn't out to break the rules. That doesn't mean she hasn't left plenty of them crumbled in her wake

Interview by Matthew Schneier. Portrait by Mario Testino

Published April 4, 2013

MS: Do you believe there are rules in fashion? Do you consider yourself to be a rule breaker?

RK: I'm not interested in rules, or whether they are there or not. I do not consciously set out to break rules. I only make clothes that I myself feel are beautiful or good-looking. People maybe say that this way of feeling is against the rules.

MS: You've spoken occasionally about the constant need for newness in your work. Is newness the ultimate goal of design? How would you rank it relative to function and beauty?

RK: What new means to me is something that doesn't exist already and that I haven't seen before. The image I have made once is already no longer new to me, so you could say the goal is not to be found in eternity. Beauty and function are different things, but luckily they have a mutual connection. But the fundamental values around which I built CDG, i.e., creation and new, have no connection to beauty and function.

MS: Do you feel that the fashion industry has become too corporate?

RK: The corporateness of the fashion industry tends to take away or distort the freedom of creation.

MS: Comme des Garçons is an independent exception. What are the benefits of independence? What are the downsides?

RK: The benefit is that I am free, and I don't take notice of the downsides.

MS: Given the state of the fashion world today, do you think a designer could start out independently, as you did, and maintain that independence even while growing to a global scale? Is the world today as hospitable to designers as it was when you began?

RK: I think the fashion world has never been a comfortable, easy place to be in. I mean, in terms of always having to fight to be free to make what one wants.

MS: Where do you see the next great designer coming from?

RK: ???

MS: When you first decided to show in Paris, were you apprehensive about what the reaction would be? Did the reaction you received surprise you?

RK: I always had good reactions from people with a good eye and a vision…and very terrible reactions from those who are afraid of people who are different to others—at the beginning and even now. I have never worried about it too much.

MS: You are one of a handful of designers who generally prefer not to give interviews. Does fashion—either all fashion or your own fashion—lose something in the explanation?

RK: I don't like to explain the clothes, how I made them, the theme, et cetera. It's because the clothes are just as you see them and feel them. That's what I want…just see and feel them. How I thought about them, where any idea came from, what the process is, is not something I like talking about to people.

MS: You have a reputation for seriousness, but in private, I've heard it said that you are very funny. And your collections are distinguished in part by their wit. Is humor an important component of your work and your process?

RK: Nothing to do with the work. The path to making things is tough. The process allows no margin for being funny. It is like a hand-to-mouth world.

MS: You come to New York rarely, but you'll be traveling here more this year to design and then to unveil the newest Dover Street Market. What are your impressions of the city so far, relative to Tokyo or Paris?

RK: Nothing special. Wherever I go, my work is one…the same.

MS: At your Dover Street Market stores, you showcase the work of other designers as well as your own. Why is that important to you?

RK: I have always liked the idea of synergy and accident…the idea of sharing space with other creative people or people who have something to say. We call it beautiful chaos…anything can happen, nothing is decided.

MS: Fashion is taking another look at punk this year, as the subject of the annual Costume Institute exhibition. What does punk mean to you?

RK: The spirit of punk lies in not ingratiating oneself to preordained values nor accepting standard authority.

MS: Some have complained that fashion has stagnated; you yourself have said that the media has enabled uninteresting fashion to thrive. Can this situation change? What would allow that to happen?

RK: I doubt the situation can change. It's because in the world where money rules, the appreciation of the value of true creation is low.

MS: Are advertisers too powerful now in the way that they dictate fashion coverage?

RK: Yes.

MS: Your Fall 2012 "flat" collection has been incredibly influential, and many are noting elements of it reverberating through several Fall '13 collections. Are you aware of this borrowing? Do you consider imitation the sincerest form of flattery, or disappointing?

RK: I am not really aware of this and not too interested either.

MS: How would you like to be remembered?

RK: I want to be forgotten.

http://www.style.com/trendsshopping/stylenotes/040113_Style_Print_Rei_Kawakubo_Comme_Des_Garcons/

Chaos Theory

Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons says she isn't out to break the rules. That doesn't mean she hasn't left plenty of them crumbled in her wake

Interview by Matthew Schneier. Portrait by Mario Testino

Published April 4, 2013

MS: Do you believe there are rules in fashion? Do you consider yourself to be a rule breaker?

RK: I'm not interested in rules, or whether they are there or not. I do not consciously set out to break rules. I only make clothes that I myself feel are beautiful or good-looking. People maybe say that this way of feeling is against the rules.

MS: You've spoken occasionally about the constant need for newness in your work. Is newness the ultimate goal of design? How would you rank it relative to function and beauty?

RK: What new means to me is something that doesn't exist already and that I haven't seen before. The image I have made once is already no longer new to me, so you could say the goal is not to be found in eternity. Beauty and function are different things, but luckily they have a mutual connection. But the fundamental values around which I built CDG, i.e., creation and new, have no connection to beauty and function.

MS: Do you feel that the fashion industry has become too corporate?

RK: The corporateness of the fashion industry tends to take away or distort the freedom of creation.

MS: Comme des Garçons is an independent exception. What are the benefits of independence? What are the downsides?

RK: The benefit is that I am free, and I don't take notice of the downsides.

MS: Given the state of the fashion world today, do you think a designer could start out independently, as you did, and maintain that independence even while growing to a global scale? Is the world today as hospitable to designers as it was when you began?

RK: I think the fashion world has never been a comfortable, easy place to be in. I mean, in terms of always having to fight to be free to make what one wants.

MS: Where do you see the next great designer coming from?

RK: ???

MS: When you first decided to show in Paris, were you apprehensive about what the reaction would be? Did the reaction you received surprise you?

RK: I always had good reactions from people with a good eye and a vision…and very terrible reactions from those who are afraid of people who are different to others—at the beginning and even now. I have never worried about it too much.

MS: You are one of a handful of designers who generally prefer not to give interviews. Does fashion—either all fashion or your own fashion—lose something in the explanation?

RK: I don't like to explain the clothes, how I made them, the theme, et cetera. It's because the clothes are just as you see them and feel them. That's what I want…just see and feel them. How I thought about them, where any idea came from, what the process is, is not something I like talking about to people.

MS: You have a reputation for seriousness, but in private, I've heard it said that you are very funny. And your collections are distinguished in part by their wit. Is humor an important component of your work and your process?

RK: Nothing to do with the work. The path to making things is tough. The process allows no margin for being funny. It is like a hand-to-mouth world.

MS: You come to New York rarely, but you'll be traveling here more this year to design and then to unveil the newest Dover Street Market. What are your impressions of the city so far, relative to Tokyo or Paris?

RK: Nothing special. Wherever I go, my work is one…the same.

MS: At your Dover Street Market stores, you showcase the work of other designers as well as your own. Why is that important to you?

RK: I have always liked the idea of synergy and accident…the idea of sharing space with other creative people or people who have something to say. We call it beautiful chaos…anything can happen, nothing is decided.

MS: Fashion is taking another look at punk this year, as the subject of the annual Costume Institute exhibition. What does punk mean to you?

RK: The spirit of punk lies in not ingratiating oneself to preordained values nor accepting standard authority.

MS: Some have complained that fashion has stagnated; you yourself have said that the media has enabled uninteresting fashion to thrive. Can this situation change? What would allow that to happen?

RK: I doubt the situation can change. It's because in the world where money rules, the appreciation of the value of true creation is low.

MS: Are advertisers too powerful now in the way that they dictate fashion coverage?

RK: Yes.

MS: Your Fall 2012 "flat" collection has been incredibly influential, and many are noting elements of it reverberating through several Fall '13 collections. Are you aware of this borrowing? Do you consider imitation the sincerest form of flattery, or disappointing?

RK: I am not really aware of this and not too interested either.

MS: How would you like to be remembered?

RK: I want to be forgotten.

Adrian Joffe, Tending the Garden of Comme des Garçons

Adrian Joffe, Tending the Garden of Comme des Garçons

SOURCE: BOF

Adrian Joffe, Tending the Garden of Comme des Garçons

BY VIKRAM ALEXEI KANSARA 28 SEPTEMBER, 2013

Comme des Garçons has quietly grown a global multi-brand fashion business that now generates $220 million in revenue per year. BoF talks to Adrian Joffe — president of Comme des Garçons International, retail guru behind Dover Street Market and a member of the recently launched BoF 500 — about tending the precious root of creativity from which the company's unconventional collections and business strategies both derive.

LONDON, United Kingdom — For Adrian Joffe, president of Comme des Garçons International and retail guru behind Dover Street Market — a shopping mecca in London’s Mayfair that’s part brand flagship, part luxury bazaar — building a fashion business is more like tending a garden than tuning an engine. “Rei Kawakubo created the company on the basic value of creation and everything else branches from that one root she planted. Creation stagnates without change. So you have to constantly grow and change, that is our goal. It’s natural, yet it’s also controlled.”

When we meet at the Rose Bakery on the top floor of Dover Street Market, Joffe is visibly excited for the store’s bi-annual tachiagari (“beginning” in Japanese). After three days of closure and re-construction, the six-storey building has just been reborn with a slew of tantalising new collections, installations and spaces created by designers including Jil Sander, Chitose Abe of Sacai, Delfina Delettrez and Kei Ninomiya (Rei Kawakubo’s newest protégé, whose line Noir Kei Ninomiya launched last Spring in Japan and has just arrived in Europe). The entrance to the store now showcases past issues of Comme des Garçons Six, the cult magazine published from 1988 to 1991. “It’s mad. Crazy stuff,” exclaims Joffe, with real thrill in his eyes. But closing the store to make radical changes every season is only one of the ways in which Dover Street Market has rewritten the conventional rules of luxury retail.

While most luxury fashion companies have been pouring money into temple- like flagship stores, specifically designed to deliver an unadulterated, monobrand experience, Dover Street Market — inspired by the now defunct Kensington Market, a three-storey indoor market that over the years, catered to various sub-cultural waves of hippies, punks, new romantics, metal-heads, ravers and goths — offers an unusual blend of products by both Comme des Garçons and a wide range of other brands, from Azzedine Alaïa and Céline by Phoebe Philo to Tokyo streetwear label Sunsea. What’s more, the store is housed in a former office space, split across six storeys connected only by a small elevator and a concrete stairwell, making it challenging to navigate. Menswear and womenswear collections are interspersed, confusing many newcomers. And while brands like Acne and APC have since followed Dover Street Market to this quiet stretch of Mayfair, the store is situated in what remains a low-traffic area, away from traditional luxury shopping areas like Bond Street.

But these seemingly off-kilter decisions flow directly from that initial root which Rei Kawakubo planted at the genesis of Comme des Garçons, in 1973. “It all comes from the same source: the desire to create something different. Our kachikan, or sense of values, goes into everything the company does. Not just clothes but everything. It has to be new. It has to be creative,” says Joffe.

“Every shop we do is new, every interior different to the last one; communication through direct mailings is based on one-year collaborations with artists. Our retail strategies, such as Dover Street Market or the Guerrilla Stores, are completely new,” he continues, referring to the unconventional, temporary stores selling products from previous seasons which Comme des Garçons opened and subsequently closed in cities like Reykjavik, Warsaw, Barcelona, Singapore, Stockholm, Athens, Beirut and Los Angeles.

“Berlin was the first Guerilla Store. I had all this stock, dead stock, things like perfume bottles, it was always in our warehouse… We made rules like proper guerillas in the jungle, always moving. And we had a maximum limit on what people could spend in the store: $2,000,” he recalls. At another brand, this kind of excess inventory from past seasons might have ended up at a conventional outlet store. Joffe managed to turn it into a novel and compelling retail experience.

Indeed, under Kawakubo and Joffe’s guidance, Comme des Garçons’kachikan of creation goes hand-in-hand with a sense of pragmatism and business savvy.

During the recession of 2008, when many fashion companies were desperately slashing prices, Comme des Garçons took a different approach, launching Black, a line reprising best-selling styles from the brand’s archive at reduced price points.

Earlier this year, Comme des Garçons announced that the New York outpost of Dover Street Market would be housed, well off the beaten luxury track, in a seven storey neoclassical building at the corner of 30th Street and Lexington Avenue, an area best known for its curry houses and the South Asian taxi drivers they attract. “Of course, we can’t afford Fifth Avenue or Madison Avenue,” says Joffe. “It’s pragmatism and it’s new. It’s exactly that mix.”

Mixing pure creativity with business savvy isn’t always easy to do, however. “Very hard, very hard, very hard,” says Joffe. “That’s the dilemma [Rei Kawakubo] has and I have as well. The ways to make money and grow internationally depend a lot on her. I can’t do anything on my own… I can’t just go and make shops and build franchises. We’re very much [working] in sync. At Dover Street Market, everything visual is her, but because it’s growing and she’s got limited time, she leaves me more and more things: what we buy, how we do the business. But it has to be within the kachikan.”

Difficult as it may be, the approach is clearly working. Comme des Garçons currently generates about $220 million a year in revenues, according to numbers provided by the company, and has attracted a cult-like global following. “Our core business is with diehard fans. We produce at least 95 percent of what is shown on the runway,” says Joffe.

But critically, the company’s more accessible offerings feel equally imbued with Comme des Garçons’ kachikan of creativity as the brand’s main line. “We never liked the idea of diffusion because it kind of waters things down. It dilutes the idea. When you think of every single diffusion line, the name is shorter: Ralph Lauren becomes RL, Donna Karan becomes DKNY. When we did a second line for Comme des Garçons we deliberately made the title longer — Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons — because it wasn’t a diffusion line, it was an extension: the thing that comes off the real thing, so you keep the spirit. The concept behind it is not lesser than the first Comme des Garçons line.”

Even the brand’s fragrances can be highly conceptual and come with bold manifestos. In 1998, the brand, famously, released it’s first “anti-perfume,” Odeur 53, a blend of notes including “oxygen, flash of metal, nail polish and burnt rubber.” The company entered into what Joffe calls a “partial licensing” agreement with Barcelona-based Puig in 2002. “We do the perfumes, we do the boxes and Rei does all the graphics, and they produce it and sell it only to fragrance stores.” But he found a clever way to keep doing the brand’s more conceptual scents, thereby sustaining the kachikan, even in fragrance. “We divided the logo. We gave [Puig] Comme des Garçons Parfums, but we made a new label, Comme des Garçons Parfums Parfums, for all the weird things. No one knows this, but you will see Parfums Parfums [on some bottles] and on the other ones, you’ll see Parfums. It’s kind of a revolutionary license really.”

Play, a range of basics, including t-shirts, sweatshirts, knitwear and canvas footwear, is one of the company’s most lucrative lines, bringing in 12 percent of overall revenue. “Play was totally a business decision. We didn’t know it was going to be so amazing,” says Joffe. But with its quirky, bug-eyed heart logo, developed in collaboration with New York graphic artist Filip Pagowski, even Play manages to embody the creative spirit of Comme des Garçons.

Indeed, Comme des Garçons’ brand architecture is less like architecture and more like an ecosystem, where a dense forest of brand extensions and product lines can grow freely and directly off the main Comme des Garçons root, without defined hierarchies. “We keep things on a parallel level,” says Joffe. “We can’t grow deeply, we’re not big enough or rich enough to open flagship stores around the world like multi-national corporations, so we have to grow the company laterally. That’s why we’ve got 17 brands,” he continues. “We’ve just got to continue, organically and naturally. Slowly, slowly, little growth. We don’t want to double overnight. We’ve never had investors or anything like that.”

In fact, Rei Kawakubo alone still owns the vast majority of Comme des Garçons KK, the Japan-based parent company which owns the Paris-based Comme des Garçons International, which in turn, owns 100 percent of Dover Street Market International, Comme des Garçons SAS, Comme des Garçons New York and the overwhelming majority of Comme des Garçons Parfum SA.

But how much can this ecosystem grow before the connection to the original root planted by Kawakubo is weakened?

“There’s the danger of dissipation,” says Joffe. “How big can you get? Already Rei is worried… Because how do you keep that strength when you are growing? It’s a big dilemma. And there’s also the effect of her having to, one day, slow down a bit… Even Rei is not immortal.”

The company now employs over 800 people. “Most people stay forever; it’s like a family because of the strength of the belief system,” says Joffe. But, in particular, designers Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara, Fumito Ganryu and Kei Ninomiya have been instrumental in extending the company’s brand ecosystem (Tao closed in 2011, but Kurihara continues to design the Tricot Comme des Garçons label.)

In the future, might one or more of them tend Kawakubo’s original root?

“It depends on who you get to take over. I think it’s got amazing potential. Comme des Garçons is organic. But I think, without doubt, it’s going to change. Because once she’s not there, for sure, it’s going to be different.”

Adrian Joffe, Tending the Garden of Comme des Garçons

BY VIKRAM ALEXEI KANSARA 28 SEPTEMBER, 2013

Comme des Garçons has quietly grown a global multi-brand fashion business that now generates $220 million in revenue per year. BoF talks to Adrian Joffe — president of Comme des Garçons International, retail guru behind Dover Street Market and a member of the recently launched BoF 500 — about tending the precious root of creativity from which the company's unconventional collections and business strategies both derive.

LONDON, United Kingdom — For Adrian Joffe, president of Comme des Garçons International and retail guru behind Dover Street Market — a shopping mecca in London’s Mayfair that’s part brand flagship, part luxury bazaar — building a fashion business is more like tending a garden than tuning an engine. “Rei Kawakubo created the company on the basic value of creation and everything else branches from that one root she planted. Creation stagnates without change. So you have to constantly grow and change, that is our goal. It’s natural, yet it’s also controlled.”

When we meet at the Rose Bakery on the top floor of Dover Street Market, Joffe is visibly excited for the store’s bi-annual tachiagari (“beginning” in Japanese). After three days of closure and re-construction, the six-storey building has just been reborn with a slew of tantalising new collections, installations and spaces created by designers including Jil Sander, Chitose Abe of Sacai, Delfina Delettrez and Kei Ninomiya (Rei Kawakubo’s newest protégé, whose line Noir Kei Ninomiya launched last Spring in Japan and has just arrived in Europe). The entrance to the store now showcases past issues of Comme des Garçons Six, the cult magazine published from 1988 to 1991. “It’s mad. Crazy stuff,” exclaims Joffe, with real thrill in his eyes. But closing the store to make radical changes every season is only one of the ways in which Dover Street Market has rewritten the conventional rules of luxury retail.

While most luxury fashion companies have been pouring money into temple- like flagship stores, specifically designed to deliver an unadulterated, monobrand experience, Dover Street Market — inspired by the now defunct Kensington Market, a three-storey indoor market that over the years, catered to various sub-cultural waves of hippies, punks, new romantics, metal-heads, ravers and goths — offers an unusual blend of products by both Comme des Garçons and a wide range of other brands, from Azzedine Alaïa and Céline by Phoebe Philo to Tokyo streetwear label Sunsea. What’s more, the store is housed in a former office space, split across six storeys connected only by a small elevator and a concrete stairwell, making it challenging to navigate. Menswear and womenswear collections are interspersed, confusing many newcomers. And while brands like Acne and APC have since followed Dover Street Market to this quiet stretch of Mayfair, the store is situated in what remains a low-traffic area, away from traditional luxury shopping areas like Bond Street.

But these seemingly off-kilter decisions flow directly from that initial root which Rei Kawakubo planted at the genesis of Comme des Garçons, in 1973. “It all comes from the same source: the desire to create something different. Our kachikan, or sense of values, goes into everything the company does. Not just clothes but everything. It has to be new. It has to be creative,” says Joffe.

“Every shop we do is new, every interior different to the last one; communication through direct mailings is based on one-year collaborations with artists. Our retail strategies, such as Dover Street Market or the Guerrilla Stores, are completely new,” he continues, referring to the unconventional, temporary stores selling products from previous seasons which Comme des Garçons opened and subsequently closed in cities like Reykjavik, Warsaw, Barcelona, Singapore, Stockholm, Athens, Beirut and Los Angeles.

“Berlin was the first Guerilla Store. I had all this stock, dead stock, things like perfume bottles, it was always in our warehouse… We made rules like proper guerillas in the jungle, always moving. And we had a maximum limit on what people could spend in the store: $2,000,” he recalls. At another brand, this kind of excess inventory from past seasons might have ended up at a conventional outlet store. Joffe managed to turn it into a novel and compelling retail experience.

Indeed, under Kawakubo and Joffe’s guidance, Comme des Garçons’kachikan of creation goes hand-in-hand with a sense of pragmatism and business savvy.

During the recession of 2008, when many fashion companies were desperately slashing prices, Comme des Garçons took a different approach, launching Black, a line reprising best-selling styles from the brand’s archive at reduced price points.

Earlier this year, Comme des Garçons announced that the New York outpost of Dover Street Market would be housed, well off the beaten luxury track, in a seven storey neoclassical building at the corner of 30th Street and Lexington Avenue, an area best known for its curry houses and the South Asian taxi drivers they attract. “Of course, we can’t afford Fifth Avenue or Madison Avenue,” says Joffe. “It’s pragmatism and it’s new. It’s exactly that mix.”

Mixing pure creativity with business savvy isn’t always easy to do, however. “Very hard, very hard, very hard,” says Joffe. “That’s the dilemma [Rei Kawakubo] has and I have as well. The ways to make money and grow internationally depend a lot on her. I can’t do anything on my own… I can’t just go and make shops and build franchises. We’re very much [working] in sync. At Dover Street Market, everything visual is her, but because it’s growing and she’s got limited time, she leaves me more and more things: what we buy, how we do the business. But it has to be within the kachikan.”

Difficult as it may be, the approach is clearly working. Comme des Garçons currently generates about $220 million a year in revenues, according to numbers provided by the company, and has attracted a cult-like global following. “Our core business is with diehard fans. We produce at least 95 percent of what is shown on the runway,” says Joffe.

But critically, the company’s more accessible offerings feel equally imbued with Comme des Garçons’ kachikan of creativity as the brand’s main line. “We never liked the idea of diffusion because it kind of waters things down. It dilutes the idea. When you think of every single diffusion line, the name is shorter: Ralph Lauren becomes RL, Donna Karan becomes DKNY. When we did a second line for Comme des Garçons we deliberately made the title longer — Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons — because it wasn’t a diffusion line, it was an extension: the thing that comes off the real thing, so you keep the spirit. The concept behind it is not lesser than the first Comme des Garçons line.”

Even the brand’s fragrances can be highly conceptual and come with bold manifestos. In 1998, the brand, famously, released it’s first “anti-perfume,” Odeur 53, a blend of notes including “oxygen, flash of metal, nail polish and burnt rubber.” The company entered into what Joffe calls a “partial licensing” agreement with Barcelona-based Puig in 2002. “We do the perfumes, we do the boxes and Rei does all the graphics, and they produce it and sell it only to fragrance stores.” But he found a clever way to keep doing the brand’s more conceptual scents, thereby sustaining the kachikan, even in fragrance. “We divided the logo. We gave [Puig] Comme des Garçons Parfums, but we made a new label, Comme des Garçons Parfums Parfums, for all the weird things. No one knows this, but you will see Parfums Parfums [on some bottles] and on the other ones, you’ll see Parfums. It’s kind of a revolutionary license really.”

Play, a range of basics, including t-shirts, sweatshirts, knitwear and canvas footwear, is one of the company’s most lucrative lines, bringing in 12 percent of overall revenue. “Play was totally a business decision. We didn’t know it was going to be so amazing,” says Joffe. But with its quirky, bug-eyed heart logo, developed in collaboration with New York graphic artist Filip Pagowski, even Play manages to embody the creative spirit of Comme des Garçons.

Indeed, Comme des Garçons’ brand architecture is less like architecture and more like an ecosystem, where a dense forest of brand extensions and product lines can grow freely and directly off the main Comme des Garçons root, without defined hierarchies. “We keep things on a parallel level,” says Joffe. “We can’t grow deeply, we’re not big enough or rich enough to open flagship stores around the world like multi-national corporations, so we have to grow the company laterally. That’s why we’ve got 17 brands,” he continues. “We’ve just got to continue, organically and naturally. Slowly, slowly, little growth. We don’t want to double overnight. We’ve never had investors or anything like that.”

In fact, Rei Kawakubo alone still owns the vast majority of Comme des Garçons KK, the Japan-based parent company which owns the Paris-based Comme des Garçons International, which in turn, owns 100 percent of Dover Street Market International, Comme des Garçons SAS, Comme des Garçons New York and the overwhelming majority of Comme des Garçons Parfum SA.

But how much can this ecosystem grow before the connection to the original root planted by Kawakubo is weakened?

“There’s the danger of dissipation,” says Joffe. “How big can you get? Already Rei is worried… Because how do you keep that strength when you are growing? It’s a big dilemma. And there’s also the effect of her having to, one day, slow down a bit… Even Rei is not immortal.”

The company now employs over 800 people. “Most people stay forever; it’s like a family because of the strength of the belief system,” says Joffe. But, in particular, designers Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara, Fumito Ganryu and Kei Ninomiya have been instrumental in extending the company’s brand ecosystem (Tao closed in 2011, but Kurihara continues to design the Tricot Comme des Garçons label.)

In the future, might one or more of them tend Kawakubo’s original root?

“It depends on who you get to take over. I think it’s got amazing potential. Comme des Garçons is organic. But I think, without doubt, it’s going to change. Because once she’s not there, for sure, it’s going to be different.”

Adrian Joffe: The Idea of COMME des GARÇONS

Adrian Joffe: The Idea of COMME des GARÇONS

SOURCE: HYPEBEAST

Adrian Joffe: The Idea of COMME des GARÇONS

When Rei Kawakubo presented her first show in Paris under the name ‘COMME des GARÇONS’ in 1981, it was received as a ground breaking collection. However not everyone in the Paris fashion system was ready for this change as she approached the fundamental core of the fashion system from a much different angle. Many collections later, COMME des GARÇONS has proved its worth in becoming one of the most influential fashion brands to emerge. That particular collection several decades ago ended the French Fashion Syndicate’s influence in the fashion industry and sparked off a new era of creation and brand management.

As the emerging Chinese market grows leaps and bounds every few months, the fashion hungry recently enjoyed a great boost thanks to the partnering of COMME des GARÇONS and I.T on the creation of I.T Beijing Market. Sharing the spotlight with another influential Japanese brand in A Bathing Ape, the two will spearhead the foundation of progressive fashion in China.

At the recent opening, we spoke with COMME des GARÇONS International’s President and Rei Kawakubo’s husband Adrian Joffe and discussed the importance of having a coherent identity, the notion of creation, Kawakubo’s fundamental beliefs and the common misconceptions of COMME des GARÇONS and Rei Kawakubo.

Interview: Edward Chiu

Text: Eugene Kan

Photography: Louis Lau

Interview with Adrian Joffe

Rei Kawakubo’s first collection “Lace” which debuted in Paris, 1981, marked the end of the French Fashion Syndicate’s influence in the fashion industry and began a new era of radical fashion. Did she achieve this by not referencing the old but by creating the new? Or simply the will to work against the fundamental core of the fashion system, which fashion has to be beautiful?

It’s always been the aim of not doing like everybody else or rather searching to make things that didn’t exist before. She basically founded the company on the premise of creation. You can see it like a tree, the roots won’t change but the branches will keep on growing, therefore the fundamental spirit has always stayed the same. Maybe sometimes, her creation is also a reaction to something, so in a way your second question does place into action. I remember about 13 years ago, she visited New York and she saw a lot of black in the GAP stores on every corner and was very astonished as the combination of fast fashion and black was not something she expected. She used mostly Black in ‘81 when the color wasn’t used at all in high fashion, so she was very shocked and said that after 20 years, suddenly everything turned black and gothic. As a reaction to that, she created her next collection “Bumps”, so in some ways it can be true. Sometimes its the reaction against what she sees, experiences and the feeling of shock or anger which can spark off another collection. So I think it’s a mixture of one and two, it has to be a mixture.

Rei Kawakubo has always challenged fashion norms such as fusing masculine and feminine motifs, introducing the distorted shapes and cuts in her silhouettes – specifically straying away from what constitutes the ideal. Design aside how do these values apply and shaped her identity as a brand?

Rei designs everything of the company. Her values permeate everything that constitutes the brand; The clothes, the shops, the printed matter, the way the clothes look in in the shops, the name cards and the retail strategy, all cannot be separated.

Similar to British artist Rachel Whiteread’s negative space sculptures, Rei Kawakubo’s clothing is not about the object but the space around the object. Does she see this as an easier route into designing or the fact that she wants to explore where other designers have overlooked?

First of all, there’s no easy route into designing. Forty two years ago when she first started, it was maybe easier because she had never done anything before. But as time goes by, the breadth of possibilities narrows and the weight of experience becomes heavy. So it’s more and more difficult to stick with the original concept of creating something new. It’s for her own self and trying to do something that she hadn’t done before. She doesn’t really look at other artists or designers’ work, as she isn’t interested in who it is and why it is. She will look at things and images and be moved or not as the case may be but she won’t analyze or define anything. She purely feels and strives for new grounds all the time because that is what she decided to base the company she founded on. She wants to be satisfied, but she’s never satisfied. This is the trouble for her, as she can never relax and she has to live with the dissatisfaction of her own work all the time, because being satisfied for one second might mean it would not be possible to strive any more.

She once mentioned when bad taste is done by COMME des GARÇONS, it becomes good taste. Does she look out for the bad taste in life and purposely manipulate them to create a part of COMME des GARÇONS’ vision?

I think it’s really just a personal thing, she sometimes takes what most people dislike and when she does it for her, it becomes something different. She gives herself limits and borders as it’s really hard to create with unlimited space. So by taking bad taste and recreating in CDG style it becomes good taste, because it’s done by her. Every collections starts with one concept, a word or one feeling and what was interesting to her in that particular moment.

It is known that Japanese designers such as herself were not happy to be branded as the “Japanese” back in the 1980s. Can you explain why this was the case? And also what is the reason behind the fascinations of death, shapes and black amongst the Japanese designers?

We cannot answer questions about the so-called “Japanese designers”. It was a mere accident that Rei was born in Japan.

All of the early Japanese designers who entered the Paris fashion system belonged to the post-war generation, and were taught whatever Western was acceptable and good. Was this a major impact in her work? And was it hard working with these ethnic boundaries in mind?

She never gave herself any ethnic boundaries, nor let them interfere with her work. From the beginning, she dispensed with any preconceived notions about western and eastern social mores and cultures, as all these things are irrelevant to her world. I strongly believe her work is at the highest possible level of creativity; What one would call pure creation perhaps, as she deliberately casts away all questions of upbringing, nationality, sociology and the like. So many times it comes from just from a feeling, an emotion, not a concrete reference.

Many Japanese designers are reluctant to show outside of their domestic confines. Is this a limiting factor in Japanese fashion?

To be honest, I have no idea about the Japanese designers in general. Although I imagine that Japanese designers, in not showing outside their domestic confines, are no different to Indian, Brazilian, Ethiopian or Russian designers who show only in their countries. I don’t think it is any more or less true about so called Japanese designers. I think it is a fallacy that Japanese designers are any less international than any other countries’ designers. I also think that any perceived similarities between designers from the same country are purely superficial, if not entirely accidental.

Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara and Fumito Ganryu all have their own unique label under the COMME des GARÇONS family. Does Rei have any sort of creative direction over them? Or are they in full control to expand the aesthetics of the COMME des GARÇONS world?

100% creative freedom. Rei feels that they won’t be able to create if they don’t have creative freedom because she, for herself, needs creative freedom. Therefore she can’t give herself creative freedom and not give that to others. For her, the reason why she wants to create is in order to be free. She’ll let them produce whatever they like. So yes, completely creative freedom and no interference.

Is the majority of the internal COMME des GARÇONS design team Japanese? If so is it because of an inherent Japanese sensibility that makes them best suited for the brand?

There are only four designers at COMME des GARÇONS. Rei, Junya, Tao and Ganryu. The so-called team is called patterners. Most are Japanese not because of any policy but because of language. But we have more and more patterners and other workers now coming through from China and Korea. We welcome this, as we do not think Japanese sensibility has anything to do with anything and true creation knows no boundaries.

How does the PLAY line incorporate into COMME des GARÇONS? Does it lessen the design achievements of the rest of the other labels by relying solely on graphics?

Not at all, it doesn’t lessen anything. PLAY started 10 years ago and the idea of PLAY is creative but playful. It was a collection, created by not designing; it was the antithesis of design, based on prototypical forms. For her it was a fresh direction, as before her designs had to be new, but this time the idea itself was new for COMME des GARÇONS to do a collection that wasn’t designed, that it was only a t-shirt with one mark. There was only a one prototype, but with no design. Everything from graphics to shop, everything is an expression. In a way it is graphic, but it doesn’t lessen anything. It only adds to the expression of the company where everything she does its a way of expressing the values.

When it comes to collaborations, how important is it that the other party has longevity? Are newer artists/creative less able to enter the collaboration fold?

There’s no point to collaborate with another designer or artist unless there’s something that can be found in between. For example, we don’t make swimwear so we collaborated with Speedo who is the best swimwear makers. So there has to be some meaning to it. So many collaborations these days are meaningless, therefore we try to find collaborators who can have an added value for both parties. So the first collaboration we did was with Vivienne Westwood fifteen years ago. It was a shared philosophy, creation and freedom of expression. We hope for accidents and unexpected synergies that can be created through our collaborations.

Many established/high-end designer labels have gone the route of developing “Made for China” collections, what are your thoughts on this?

That is fine for them, but there are no plans for COMME des GARÇONS to make any specific collections for the China market, as we think of China and the rest of the world as one.

How damaging is the problem of counterfeit products in both China and on a global scale?

It’s a major pain in the ass, but the real thing is undoubtedly the best. The government should definitely intervene and take action against the people who copy.

With the expansive scope of COMME des GARÇONS now, how much input does Rei maintain? Some things are beyond her control, but how does she deal with that?

Rei maintains total control of everything from the initial idea to the final outcome, especially for everything visual. And for the business side of things, she leaves a lot of that to me.

As Rei’s retail space concept has always been a continuation of her own ideals, how much has that changed since her early beginnings? And how will COMME des GARÇONS adapt to the online retail boom?

Her ideals have always stayed the same way and will never change. She will simply search for new ways to express her feelings, thoughts and ideas. However, she won’t be adapting any time soon to the recent online retail phenomenon, although we’re not ignoring that fact and have started some experiments. On the other hand, our Dover Street Market online shop’s sales figures have increased by 250% from 2009!

How much longer can COMME des GARÇONS remain with a limited online presence? Why has the brand stayed offline for so long?

She’s experimenting with each outlet. For example she’s letting me expand the Dover Street Market online shop and she just launched the COMME des GARÇONS website, but she doesn’t show anything obvious, just image and information. The time will come, but she takes her time with technology because she doesn’t feel it yet. She believes clothes have to be touched, so I doubt COMME des GARÇONS’ main collection will ever be on the website, however there are many creative possibilities which we’re looking into.

In a recent interview, Rei was quoted as being dismissive of the current crop of younger designers. Could you shed some light on what exactly she meant?

I believe you mean the interview that was published from the establishment rag known as WWD. We were rather upset if not shocked by the way they twisted the words of Rei and made it sound like she was dismissive of young designers in general. Everyone knows that Rei respects enormously all-young designers that work hard and believe in creation. COMME des GARÇONS are constantly on the lookout for creative talent to have in our multi mark shops, and anyone who knows Dover Street Market London will know we have many young designers there. She was merely making the comment about a lot of young people in general these days, not just in fashion, as they hope and expect for success too quickly and are too impatient. In her time, it took years and years before she was really able to make a proper living at making clothes. However she knows that the times are very different now and she knows how hard it is. She is in no way dismissive of young designers, as she only wants to encourage them to be strong and creative and follow their own vision. Sharing spaces with people like them is the fundamental idea behind Dover Street Market London and I.T Beijing Market.

Throughout the years, Rei has sparingly offered English language interviews, in reality is she less of a secretive person as many may believe?

This is another fallacy. Rei did at least ten or fifteen interviews in 2010 alone. We did five in Beijing just last week, even though WWD falsely called their particular one “rare”. What nonsense! She is not so much secretive as simply unwilling to talk about her private life and she doesn’t like being photographed. She basically doesn’t trust journalists because they often twist what she says and turn it around to make their point. She has very often been deceived by journalists in this way. The scandal mongering WWD’s article of last week is a case in point. Not only did they dare to publish a totally unauthorized photo of Rei, they also twisted many of her own words, or taking them out of context, to make them sound revelatory when they were not. For example, they made it sound that COMME des GARÇONS is for sale, which it totally isn’t. They called my 100% joke about waiting for an offer, a “half joke…”.

Looking at the current avant-garde landscape, who would you say is breaking the molds of the conventional notion of fashion?

We cannot mention anyone by name, since that would be unfair on the people who we simply may not be aware of… We can only wish anyone who works with their heart and soul and looks for something new the greatest of luck, because without creation there can be no progress.

Adrian Joffe: The Idea of COMME des GARÇONS

When Rei Kawakubo presented her first show in Paris under the name ‘COMME des GARÇONS’ in 1981, it was received as a ground breaking collection. However not everyone in the Paris fashion system was ready for this change as she approached the fundamental core of the fashion system from a much different angle. Many collections later, COMME des GARÇONS has proved its worth in becoming one of the most influential fashion brands to emerge. That particular collection several decades ago ended the French Fashion Syndicate’s influence in the fashion industry and sparked off a new era of creation and brand management.

As the emerging Chinese market grows leaps and bounds every few months, the fashion hungry recently enjoyed a great boost thanks to the partnering of COMME des GARÇONS and I.T on the creation of I.T Beijing Market. Sharing the spotlight with another influential Japanese brand in A Bathing Ape, the two will spearhead the foundation of progressive fashion in China.

At the recent opening, we spoke with COMME des GARÇONS International’s President and Rei Kawakubo’s husband Adrian Joffe and discussed the importance of having a coherent identity, the notion of creation, Kawakubo’s fundamental beliefs and the common misconceptions of COMME des GARÇONS and Rei Kawakubo.

Interview: Edward Chiu

Text: Eugene Kan

Photography: Louis Lau

Interview with Adrian Joffe

Rei Kawakubo’s first collection “Lace” which debuted in Paris, 1981, marked the end of the French Fashion Syndicate’s influence in the fashion industry and began a new era of radical fashion. Did she achieve this by not referencing the old but by creating the new? Or simply the will to work against the fundamental core of the fashion system, which fashion has to be beautiful?

It’s always been the aim of not doing like everybody else or rather searching to make things that didn’t exist before. She basically founded the company on the premise of creation. You can see it like a tree, the roots won’t change but the branches will keep on growing, therefore the fundamental spirit has always stayed the same. Maybe sometimes, her creation is also a reaction to something, so in a way your second question does place into action. I remember about 13 years ago, she visited New York and she saw a lot of black in the GAP stores on every corner and was very astonished as the combination of fast fashion and black was not something she expected. She used mostly Black in ‘81 when the color wasn’t used at all in high fashion, so she was very shocked and said that after 20 years, suddenly everything turned black and gothic. As a reaction to that, she created her next collection “Bumps”, so in some ways it can be true. Sometimes its the reaction against what she sees, experiences and the feeling of shock or anger which can spark off another collection. So I think it’s a mixture of one and two, it has to be a mixture.

Rei Kawakubo has always challenged fashion norms such as fusing masculine and feminine motifs, introducing the distorted shapes and cuts in her silhouettes – specifically straying away from what constitutes the ideal. Design aside how do these values apply and shaped her identity as a brand?

Rei designs everything of the company. Her values permeate everything that constitutes the brand; The clothes, the shops, the printed matter, the way the clothes look in in the shops, the name cards and the retail strategy, all cannot be separated.

Similar to British artist Rachel Whiteread’s negative space sculptures, Rei Kawakubo’s clothing is not about the object but the space around the object. Does she see this as an easier route into designing or the fact that she wants to explore where other designers have overlooked?

First of all, there’s no easy route into designing. Forty two years ago when she first started, it was maybe easier because she had never done anything before. But as time goes by, the breadth of possibilities narrows and the weight of experience becomes heavy. So it’s more and more difficult to stick with the original concept of creating something new. It’s for her own self and trying to do something that she hadn’t done before. She doesn’t really look at other artists or designers’ work, as she isn’t interested in who it is and why it is. She will look at things and images and be moved or not as the case may be but she won’t analyze or define anything. She purely feels and strives for new grounds all the time because that is what she decided to base the company she founded on. She wants to be satisfied, but she’s never satisfied. This is the trouble for her, as she can never relax and she has to live with the dissatisfaction of her own work all the time, because being satisfied for one second might mean it would not be possible to strive any more.

She once mentioned when bad taste is done by COMME des GARÇONS, it becomes good taste. Does she look out for the bad taste in life and purposely manipulate them to create a part of COMME des GARÇONS’ vision?

I think it’s really just a personal thing, she sometimes takes what most people dislike and when she does it for her, it becomes something different. She gives herself limits and borders as it’s really hard to create with unlimited space. So by taking bad taste and recreating in CDG style it becomes good taste, because it’s done by her. Every collections starts with one concept, a word or one feeling and what was interesting to her in that particular moment.

It is known that Japanese designers such as herself were not happy to be branded as the “Japanese” back in the 1980s. Can you explain why this was the case? And also what is the reason behind the fascinations of death, shapes and black amongst the Japanese designers?

We cannot answer questions about the so-called “Japanese designers”. It was a mere accident that Rei was born in Japan.

All of the early Japanese designers who entered the Paris fashion system belonged to the post-war generation, and were taught whatever Western was acceptable and good. Was this a major impact in her work? And was it hard working with these ethnic boundaries in mind?

She never gave herself any ethnic boundaries, nor let them interfere with her work. From the beginning, she dispensed with any preconceived notions about western and eastern social mores and cultures, as all these things are irrelevant to her world. I strongly believe her work is at the highest possible level of creativity; What one would call pure creation perhaps, as she deliberately casts away all questions of upbringing, nationality, sociology and the like. So many times it comes from just from a feeling, an emotion, not a concrete reference.

Many Japanese designers are reluctant to show outside of their domestic confines. Is this a limiting factor in Japanese fashion?

To be honest, I have no idea about the Japanese designers in general. Although I imagine that Japanese designers, in not showing outside their domestic confines, are no different to Indian, Brazilian, Ethiopian or Russian designers who show only in their countries. I don’t think it is any more or less true about so called Japanese designers. I think it is a fallacy that Japanese designers are any less international than any other countries’ designers. I also think that any perceived similarities between designers from the same country are purely superficial, if not entirely accidental.

Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara and Fumito Ganryu all have their own unique label under the COMME des GARÇONS family. Does Rei have any sort of creative direction over them? Or are they in full control to expand the aesthetics of the COMME des GARÇONS world?

100% creative freedom. Rei feels that they won’t be able to create if they don’t have creative freedom because she, for herself, needs creative freedom. Therefore she can’t give herself creative freedom and not give that to others. For her, the reason why she wants to create is in order to be free. She’ll let them produce whatever they like. So yes, completely creative freedom and no interference.

Is the majority of the internal COMME des GARÇONS design team Japanese? If so is it because of an inherent Japanese sensibility that makes them best suited for the brand?

There are only four designers at COMME des GARÇONS. Rei, Junya, Tao and Ganryu. The so-called team is called patterners. Most are Japanese not because of any policy but because of language. But we have more and more patterners and other workers now coming through from China and Korea. We welcome this, as we do not think Japanese sensibility has anything to do with anything and true creation knows no boundaries.

How does the PLAY line incorporate into COMME des GARÇONS? Does it lessen the design achievements of the rest of the other labels by relying solely on graphics?

Not at all, it doesn’t lessen anything. PLAY started 10 years ago and the idea of PLAY is creative but playful. It was a collection, created by not designing; it was the antithesis of design, based on prototypical forms. For her it was a fresh direction, as before her designs had to be new, but this time the idea itself was new for COMME des GARÇONS to do a collection that wasn’t designed, that it was only a t-shirt with one mark. There was only a one prototype, but with no design. Everything from graphics to shop, everything is an expression. In a way it is graphic, but it doesn’t lessen anything. It only adds to the expression of the company where everything she does its a way of expressing the values.

When it comes to collaborations, how important is it that the other party has longevity? Are newer artists/creative less able to enter the collaboration fold?

There’s no point to collaborate with another designer or artist unless there’s something that can be found in between. For example, we don’t make swimwear so we collaborated with Speedo who is the best swimwear makers. So there has to be some meaning to it. So many collaborations these days are meaningless, therefore we try to find collaborators who can have an added value for both parties. So the first collaboration we did was with Vivienne Westwood fifteen years ago. It was a shared philosophy, creation and freedom of expression. We hope for accidents and unexpected synergies that can be created through our collaborations.

Many established/high-end designer labels have gone the route of developing “Made for China” collections, what are your thoughts on this?

That is fine for them, but there are no plans for COMME des GARÇONS to make any specific collections for the China market, as we think of China and the rest of the world as one.

How damaging is the problem of counterfeit products in both China and on a global scale?

It’s a major pain in the ass, but the real thing is undoubtedly the best. The government should definitely intervene and take action against the people who copy.

With the expansive scope of COMME des GARÇONS now, how much input does Rei maintain? Some things are beyond her control, but how does she deal with that?

Rei maintains total control of everything from the initial idea to the final outcome, especially for everything visual. And for the business side of things, she leaves a lot of that to me.

As Rei’s retail space concept has always been a continuation of her own ideals, how much has that changed since her early beginnings? And how will COMME des GARÇONS adapt to the online retail boom?

Her ideals have always stayed the same way and will never change. She will simply search for new ways to express her feelings, thoughts and ideas. However, she won’t be adapting any time soon to the recent online retail phenomenon, although we’re not ignoring that fact and have started some experiments. On the other hand, our Dover Street Market online shop’s sales figures have increased by 250% from 2009!

How much longer can COMME des GARÇONS remain with a limited online presence? Why has the brand stayed offline for so long?

She’s experimenting with each outlet. For example she’s letting me expand the Dover Street Market online shop and she just launched the COMME des GARÇONS website, but she doesn’t show anything obvious, just image and information. The time will come, but she takes her time with technology because she doesn’t feel it yet. She believes clothes have to be touched, so I doubt COMME des GARÇONS’ main collection will ever be on the website, however there are many creative possibilities which we’re looking into.

In a recent interview, Rei was quoted as being dismissive of the current crop of younger designers. Could you shed some light on what exactly she meant?

I believe you mean the interview that was published from the establishment rag known as WWD. We were rather upset if not shocked by the way they twisted the words of Rei and made it sound like she was dismissive of young designers in general. Everyone knows that Rei respects enormously all-young designers that work hard and believe in creation. COMME des GARÇONS are constantly on the lookout for creative talent to have in our multi mark shops, and anyone who knows Dover Street Market London will know we have many young designers there. She was merely making the comment about a lot of young people in general these days, not just in fashion, as they hope and expect for success too quickly and are too impatient. In her time, it took years and years before she was really able to make a proper living at making clothes. However she knows that the times are very different now and she knows how hard it is. She is in no way dismissive of young designers, as she only wants to encourage them to be strong and creative and follow their own vision. Sharing spaces with people like them is the fundamental idea behind Dover Street Market London and I.T Beijing Market.

Throughout the years, Rei has sparingly offered English language interviews, in reality is she less of a secretive person as many may believe?

This is another fallacy. Rei did at least ten or fifteen interviews in 2010 alone. We did five in Beijing just last week, even though WWD falsely called their particular one “rare”. What nonsense! She is not so much secretive as simply unwilling to talk about her private life and she doesn’t like being photographed. She basically doesn’t trust journalists because they often twist what she says and turn it around to make their point. She has very often been deceived by journalists in this way. The scandal mongering WWD’s article of last week is a case in point. Not only did they dare to publish a totally unauthorized photo of Rei, they also twisted many of her own words, or taking them out of context, to make them sound revelatory when they were not. For example, they made it sound that COMME des GARÇONS is for sale, which it totally isn’t. They called my 100% joke about waiting for an offer, a “half joke…”.

Looking at the current avant-garde landscape, who would you say is breaking the molds of the conventional notion of fashion?

We cannot mention anyone by name, since that would be unfair on the people who we simply may not be aware of… We can only wish anyone who works with their heart and soul and looks for something new the greatest of luck, because without creation there can be no progress.

Rei Kawakubo: the first lady of fashion

Rei Kawakubo: the first lady of fashion

SOURCE: DAZED DIGITAL

Rei Kawakubo: the first lady of fashion

Ahead of Comme des Garçons AW14, we uncover an archive interview with the designer from Dazed & Confused issue 16, 1995

Text Paul Smith

In anticipation of the Comme des Garçons AW14 show on the 1st March this Paris Fashion Week, we look back at an interview Rei Kawakubo did with fellow fashion designer Paul Smith, in a special issue Smith guest edited. Never before published on Dazed Digital, the 'interview' is a snappy back-and-forth conversation between contemporaries, underpinned by Smith's clear admiration for the avant-garde designer – and Kawakubo's dry humour.

Taken from Dazed & Confused issue 16, 1995.

Kawakubo's international label Comme des Garçons, formed in Tokyo in 1973, is notably famous for setting the monochromatic style and changing the face of fashion in the early 80s. With "as never seen before" silhouettes – shapeless shapes for her simplistic tent-like shrouds poised in black austerity, her clothes are never about accentuating or revealing the body, but allowing the wearer to be who they are.

Kawakubo has always de-prettified the models who have stomped down the catwalk in a sombre wake, wearing clothes which initially had to be explained to customers on how they should be worn. The notorious black T-shirt, for example, which appeared to have four sleeves when placed flat, yet turned into a chic double tunic when worn. Comme des Garçons' hand-knit sweaters full of holes came close to punk, and appeared anarchistic at the time of 80s retentive power-dressing. She sees fashion as art, and designs sculpturally, considering the fabric first. Her minimalist, asymmetric clothes are the epitome of deconstructionalism (seams raw-edged, incompatible fabrics bonded together), inspiring a host of European designers, most notably John Galliano, Martin Margiela, Helmut Lang and Ann Demeulemeester.

Comme des Garçons' kaleidoscopically-themed women's collection for Spring Summer 96 maintains Rei Kawakubo's position at the forefront of sensationalism. Linda Evangelista, Kate Moss and Nadja Auermann wore Ronald McDonald crazy-colour, candy-floss wigs and neon knitwear on the catwalk.

Kawakubo has always run the business side of Comme des Garçons and outsells either of her Japanese peers Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto by two to one. She has won several awards, held many exhibitions and had various books written about her. Her futuristic vision; her designs for "a way of life" through clothes, furniture, architecture, interiors and perfume and the former Comme des Garçons magazine Six, (which always overlooked her clothes, in favour of features, such as a ten page piece on Gilbert and George), have all established her as one of the 20th century's most important, innovative and influential designers.

Paul Smith: Thanks for letting me interview you. I thought, if it is OK with you, I'd just ask questions that I wish people would ask me, not typical interview questions. Who is your favourite artist and why?

Rei Kawakubo: No one in particular. I am usually more attracted to the way they lived their lives rather than their actual works.

PS: I recently went to see Christo's wrapping in Berlin. Have you seen any of his work? Do you like his work? If so, why do you like it?

RK: I find his concept interesting. Recently I saw a documentary on Christo working on his latest piece in Berlin on BBC which, amazingly, we are now able to see in Japan.

PS: Have you wrapped anything yourself?

RK: Yes. I have wrapped everything conceivable on a body while making clothes.

PS: Do you get time to travel for pleasure and, if so, where do you enjoy the most? If you go on holiday do you prefer to relax, sunbathe, sail, walk or explore new places?

RK: I like to travel to places that stimulate me but I never have enough time.

PS: Is there anywhere in particular you'd love to go but just haven't had the time or opportunity?

RK: Uzbekistan.

PS: Do you fancy Disneyland?

RK: It is the last place on earth I want to visit.

PS: How important is music in your life? What type of music do you like? Do you listen to music while you work? Do you go to watch live bands? Do you go to concerts? Do you own a Walkman?

RK: I never listen to music while working nor do I go to concerts. I like the sound of silence.

PS: I think I'm right in saying that, like me, you're a great fan of Le Corbusier. Are there any living architects whose work you admire? If so, why?

RK: I like the simplicity and spaciousness of Le Corbusier.

PS: Do you find time to go to the cinema or watch videos/television? If so, what subjects do you prefer?

RK: I enjoy films which have strong visuals. I certainly do not watch horror, SF or comedy.

PS: Have you ever been involved in the making of a movie in any way?

RK: No.

PS: Do you have any plans to get involved in film in the future, or would you like to?

RK: No.

PS: What are your three favourite movies? What makes them special for you?

RK: Films by Theo Angelopoulos.

PS: Do you find time to read? Do you read Japanese or Western writers? Who is your favourite author? Did you read comics as a child?

RK: I have a tendency to buy books I want to read and they end up piling up on my desk, since I have little time to read.

PS: Do you have any sisters or brothers?

RK: Two younger brothers.

PS: Are they involved in Comme des Garçons or in fashion at all? What are their professions? Did they have an influence on your career?

RK: No, they are not involved in fashion. No, they do not influence my work.

PS: What is your earliest childhood memory? Mine was at the age of 11, incident of given bicycle.

RK: The seasons. Glaring sun and its heat. Snow piled up as high as one metre.

PS: Many people in Japan ride bicycles; do you?

RK: I prefer walking, but I have been able to ride a bicycle since I was a child.

PS: Over the years you have worked with many of the world's famous photographers. Do you take photographs? If so, do you prefer to use black and white, or colour films? Is it to record your and your friends' lives, or is it an art form?

RK: I enjoy looking at photographs but loathe being photographed. I'd rather make clothes than take photographs.

PS: Other than Japanese, what food do you enjoy?

RK: Spicy food, especially Thai.

PS: Do you cook at home?

RK: Sometimes.

PS: Have you ever eaten real English food? What do you think of it?

RK: Yes, I have eaten full English breakfast, which I like very much.

PS: Do you enjoy married life?

RK: I enjoy my life.

PS: Do you have any children?

RK: Yes, 425. They all work at Comme des Garçons.

PS: Are you an animal lover? What is your favourite animal? Do you have any pets? If so, what and how many?

RK: I like all animals, especially wolves.

PS: What do you fear the most?

RK: The next collection.

PS: What do you feel you'd still like to achieve in life?

RK: The next collection.

PS: What car do you drive?

RK: A big old Japanese car.

PS: What is your favourite month and why?

RK: The ones that do not have collections.

PS: What is your favourite number and why?

RK: Odd numbers, because they are asymmetric and strong.

PS: What is your lucky charm? Mine is a rabbit.

RK: I don't have one. I never even thought about it.

Rei Kawakubo: the first lady of fashion

Ahead of Comme des Garçons AW14, we uncover an archive interview with the designer from Dazed & Confused issue 16, 1995

Text Paul Smith

In anticipation of the Comme des Garçons AW14 show on the 1st March this Paris Fashion Week, we look back at an interview Rei Kawakubo did with fellow fashion designer Paul Smith, in a special issue Smith guest edited. Never before published on Dazed Digital, the 'interview' is a snappy back-and-forth conversation between contemporaries, underpinned by Smith's clear admiration for the avant-garde designer – and Kawakubo's dry humour.

Taken from Dazed & Confused issue 16, 1995.

Kawakubo's international label Comme des Garçons, formed in Tokyo in 1973, is notably famous for setting the monochromatic style and changing the face of fashion in the early 80s. With "as never seen before" silhouettes – shapeless shapes for her simplistic tent-like shrouds poised in black austerity, her clothes are never about accentuating or revealing the body, but allowing the wearer to be who they are.

Kawakubo has always de-prettified the models who have stomped down the catwalk in a sombre wake, wearing clothes which initially had to be explained to customers on how they should be worn. The notorious black T-shirt, for example, which appeared to have four sleeves when placed flat, yet turned into a chic double tunic when worn. Comme des Garçons' hand-knit sweaters full of holes came close to punk, and appeared anarchistic at the time of 80s retentive power-dressing. She sees fashion as art, and designs sculpturally, considering the fabric first. Her minimalist, asymmetric clothes are the epitome of deconstructionalism (seams raw-edged, incompatible fabrics bonded together), inspiring a host of European designers, most notably John Galliano, Martin Margiela, Helmut Lang and Ann Demeulemeester.

Comme des Garçons' kaleidoscopically-themed women's collection for Spring Summer 96 maintains Rei Kawakubo's position at the forefront of sensationalism. Linda Evangelista, Kate Moss and Nadja Auermann wore Ronald McDonald crazy-colour, candy-floss wigs and neon knitwear on the catwalk.

Kawakubo has always run the business side of Comme des Garçons and outsells either of her Japanese peers Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto by two to one. She has won several awards, held many exhibitions and had various books written about her. Her futuristic vision; her designs for "a way of life" through clothes, furniture, architecture, interiors and perfume and the former Comme des Garçons magazine Six, (which always overlooked her clothes, in favour of features, such as a ten page piece on Gilbert and George), have all established her as one of the 20th century's most important, innovative and influential designers.

Paul Smith: Thanks for letting me interview you. I thought, if it is OK with you, I'd just ask questions that I wish people would ask me, not typical interview questions. Who is your favourite artist and why?

Rei Kawakubo: No one in particular. I am usually more attracted to the way they lived their lives rather than their actual works.

PS: I recently went to see Christo's wrapping in Berlin. Have you seen any of his work? Do you like his work? If so, why do you like it?

RK: I find his concept interesting. Recently I saw a documentary on Christo working on his latest piece in Berlin on BBC which, amazingly, we are now able to see in Japan.

PS: Have you wrapped anything yourself?

RK: Yes. I have wrapped everything conceivable on a body while making clothes.

PS: Do you get time to travel for pleasure and, if so, where do you enjoy the most? If you go on holiday do you prefer to relax, sunbathe, sail, walk or explore new places?

RK: I like to travel to places that stimulate me but I never have enough time.

PS: Is there anywhere in particular you'd love to go but just haven't had the time or opportunity?

RK: Uzbekistan.

PS: Do you fancy Disneyland?

RK: It is the last place on earth I want to visit.

PS: How important is music in your life? What type of music do you like? Do you listen to music while you work? Do you go to watch live bands? Do you go to concerts? Do you own a Walkman?

RK: I never listen to music while working nor do I go to concerts. I like the sound of silence.

PS: I think I'm right in saying that, like me, you're a great fan of Le Corbusier. Are there any living architects whose work you admire? If so, why?

RK: I like the simplicity and spaciousness of Le Corbusier.

PS: Do you find time to go to the cinema or watch videos/television? If so, what subjects do you prefer?

RK: I enjoy films which have strong visuals. I certainly do not watch horror, SF or comedy.

PS: Have you ever been involved in the making of a movie in any way?

RK: No.

PS: Do you have any plans to get involved in film in the future, or would you like to?

RK: No.

PS: What are your three favourite movies? What makes them special for you?

RK: Films by Theo Angelopoulos.

PS: Do you find time to read? Do you read Japanese or Western writers? Who is your favourite author? Did you read comics as a child?

RK: I have a tendency to buy books I want to read and they end up piling up on my desk, since I have little time to read.

PS: Do you have any sisters or brothers?

RK: Two younger brothers.

PS: Are they involved in Comme des Garçons or in fashion at all? What are their professions? Did they have an influence on your career?

RK: No, they are not involved in fashion. No, they do not influence my work.

PS: What is your earliest childhood memory? Mine was at the age of 11, incident of given bicycle.

RK: The seasons. Glaring sun and its heat. Snow piled up as high as one metre.

PS: Many people in Japan ride bicycles; do you?

RK: I prefer walking, but I have been able to ride a bicycle since I was a child.

PS: Over the years you have worked with many of the world's famous photographers. Do you take photographs? If so, do you prefer to use black and white, or colour films? Is it to record your and your friends' lives, or is it an art form?

RK: I enjoy looking at photographs but loathe being photographed. I'd rather make clothes than take photographs.

PS: Other than Japanese, what food do you enjoy?

RK: Spicy food, especially Thai.

PS: Do you cook at home?

RK: Sometimes.

PS: Have you ever eaten real English food? What do you think of it?

RK: Yes, I have eaten full English breakfast, which I like very much.

PS: Do you enjoy married life?

RK: I enjoy my life.

PS: Do you have any children?

RK: Yes, 425. They all work at Comme des Garçons.

PS: Are you an animal lover? What is your favourite animal? Do you have any pets? If so, what and how many?

RK: I like all animals, especially wolves.

PS: What do you fear the most?

RK: The next collection.

PS: What do you feel you'd still like to achieve in life?

RK: The next collection.

PS: What car do you drive?

RK: A big old Japanese car.

PS: What is your favourite month and why?

RK: The ones that do not have collections.

PS: What is your favourite number and why?

RK: Odd numbers, because they are asymmetric and strong.

PS: What is your lucky charm? Mine is a rabbit.

RK: I don't have one. I never even thought about it.

The Misfit | Rei Kawakubo is a Japanese avant-gardist of few words, and she changed women’s fashion.

The Misfit | Rei Kawakubo is a Japanese avant-gardist of few words, and she changed women’s fashion.

SOURCE: THE NEW YORKER

The Misfit

Rei Kawakubo is a Japanese avant-gardist of few words, and she changed women’s fashion.

Kawakubo in Tokyo this year. CREDITPHOTOGRAPH BY EIICHIRO SAKATA